MMIF is an annotation format for audiovisual media as well as associated text like transcripts, closed captions and other OCR. MMIF is a JSON-LD format used to transport data between CLAMS services and is inspired by and partially based on LIF, the LAPPS Interchange Format. MMIF is pronounced mif or em-mif, or, if you like to hum, mmmmmif.

MMIF consist of three formal components in addition to this more informal specification, they are:

- The JSON schema:

- The Linked Data (JSON-LD) context:

- The Vocabularies (type hierarchies):

The JSON schema for MMIF defines the syntactic elements of MMIF and the contexts define shortcuts for URIs of the MMIF namespace. Both will be explained at length in this document in section 1. These specifications often refer to elements from the CLAMS and LAPPS Vocabularies which define concepts and their ontological relations, see section 2 for some more notes on those vocabularies.

Along with the formal specifications and documentation, our goal also includes providing a reference implementation of MMIF. Currently it is being developed in the Python programming language and it will be distributed via github (as source code) as well as via the Python Package Index (as a Python library). The package will function as a software development kit (SDK), that helps users (mostly developers) to easily use various features of MMIF in developing their own applications.

Versioning

The MMIF specification and its reference implementation (SDK) are now in pre-alpha stage, and during the current development phase, we will use 0.1.x versions. All present and future versions follow the semantic versioning specification, and use major.minor.patch version scheme. All formal components (this document, JSON schema, JSON-LD context, and CLAMS vocabulary) share the same version number, while the SDK shares major and minor numbers with the specification version. That is,

- A change in a single component of the specification will increase version numbers of other components as well, and thus some components can be identical to their immediate previous version.

- A specific version of the SDK is tied to certain versions of the specification, and thus the applications based on different versions of SDK may not be compatible to each other, and may not be used together in a single pipeline.

1. The structure of MMIF files

The basic idea is that in essence a MMIF file needs to represent two things:

- Media like texts, videos, images and audio recordings.

- Annotations over those media representing information that was added by processing the media.

Annotations are always stored separately from the media. They can be directly linked to a slice in the media (a string in a text, a shape in an image, or a time frame in a video or audio). Annotations can also refer to other annotations, for example to specify relations between text strings. More specifically, a MMIF file contains a context, metadata, a list of media and a list of annotation views, where each view contains a list of annotation types like Segment, BoundingBox, VideoObject or NamedEntity. The top-level structure of a MMIF file is as follows:

{

"@context": "http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/context/miff.json",

"metadata": { },

"media": [ ],

"views": [ ]

}

The following sub sections describe the values of these four properties.

1.1. The @context property

In JSON-LD, keys used in the various dictionaries, including the top-level dictionary show in section 1, need to be associated with a full URI. To keep the files from overflowing with full URIs we can use a context file that defines how short names like media can be expanded to a full URI like http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocab/mmif/media. The value here is the fixed URL http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/context/miff.json which is a JSON-LD context document that points to the MMIF vocabulary URI http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocab/mmif. This vocabulary defines the full of the keys used in the overal MMIF file, which includes the three keys in the example in section 1above (metadata, media and views) as well as many others that will be introduced below (text, annotations, properties, etcetera). It does not include elements from the semantic vocabularies of CLAMS and LAPPS, we will return to those later when we talk about annotations in views.

1.2. The metadata property

Includes any metadata associated with the file. Not heavily used for now, but we do use it to store the MMIF version used in the document.

{

"metadata": {

"mmif": "http://miff.clams.ai/0.1.0"

}

}

MMIF has many parts to it: specifications, schema, context files, vocabulary and SDK. For now we assume that these are all included under the one version number. We are considering whether there is a need for keeping separate versioning for those components (but would liek to avoid that).

Note that untill recently the metadata also had a contains property which included an overview of the data in all views. This was removed to avoid redundancies and potential conflicts.

1.3. The media property

The value is a list of media specifications where each media element has an identifier, a type, a location and optional metadata. Here is an example for a video and its transcript:

{

"media": [

{

"id": "m1",

"type": "video",

"mime": "video/mp4",

"location": "/var/archive/video-0012.mp4"

},

{

"id": "m2",

"type": "text",

"mime": "text/plain",

"location": "/var/archive/video-0012-transcript.txt"

}

]

}

The type is one of text, video, audio or image, but in the future more types may be added. The other properties store the MIME type and the location of the media file, the latter of which is a URL or a local path to a file. Alternatively, and for text only, the media could be inline, in which case the element is represented as in the text property in LIF, which is a JSON value object containing a @value key and optionally a @language key:

{

"media": [

{

"id": "m1",

"type": "video",

"mime": "video/mp4",

"location": "/var/archive/video-0012.mp4"

},

{

"id": "m2",

"type": "text",

"text": {

"@value": "Fido barks",

"@language": "en" }

}

]

}

The value associated with @value is a string and the value associated with @language follows the rules in BCP47, which for our current purposes boils down to using the two-character ISO 639 code. With inline text there is no MIME type.

With LAPPS and LIF, there was only one medium, namely the text source, and how that source came into being was not represented in any way. For MMIF the situation is different in that there are four kinds of media and for each one there can be many instances in a MMIF document. And some of those media can actually be the result of processing other media, for example when we recognize a text box in an image and run OCR over that box. This introduces a need to elaborate on the representation of media, but we will return to this in section 1.5 after we have introduced annotations.

1.4. The views property

This is where all the annotations and associated metadata live. Views contain structured information about media but are separate from those media. The value of views is a JSON array of view objects where each view specifies what media the annotation is over, what information it contains and what service created that information. To that end, each view has four properties: id, @context, metadata and annotations.

{

"views": [

{

"id": "v1",

"@context": "http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/context/vocab-clams.json",

"metadata": { },

"annotations": [ ]

}

]

}

Each view has a unique identifier. Annotation elements in the view have identifiers unique to the view and these elements can be uniquely referred to from outside the view by using the view identifier and the annotation element identifier. For example, if the view above had an annotation with identfier “a8” then it could be referred to from outside the view by “v1:a8”.

The @context property defines the vocabulary contex for the annotations in the view. Recall the @context property in section 1.1, which allowed terms like metadata to be expanded to a full URI like http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocab/mmif/metadata. That context was not set up to deal with the annotation categories that are used in a view. For example, CLAMS applications may use an annotation type named Segment and we want to use the linked data aspect of JSON-LD to link that that term to a URI that contains a definition of the type, so we want to expand Segment to http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocab/Segment and the CLAMS context file has the definitions to allow for that. Note that the example here points the CLAMS vocabulary, but for views with results from LAPPS services we can use the LAPPS vocabulary context. See section 2 for more on the vocabulary.

Before describing the metadata and annotation we list a few general principles relevant to views:

- There is no limit to the number of views.

- Services may create as many new views as they want.

- Services may not add information to existing views, that is, views are read only, which has many advantages at the cost of some redundancy. Since views are read-only, services may not overwrite or delete information in existing views. This holds for the view’s metadata as well as the annotations.

- Annotations in views have identifiers that are unique to the view. Views have identifiers that uniquely define them relative to other views.

- Views should not mix annotations from CLAMS and LAPPS services.

- Each view is associated with a semantic context.

1.4.1. The view’s metadata property

This property contains information about the annotations in a view. Here is an example for a view over a video with medium identifier “m3” with segments added by the CLAMS bars-and-tones tool:

{

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/Segment": {

"unit": "seconds"

}

},

"medium": "m3",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.ai/bars-and-tones/1.0.5"

}

The contains dictionary has keys that refer to annotation objects in the CLAMS or LAPPS vocabulary or properties of those annotation objects (they can also refer to user-defined objects or properties) and they indicate the kind of annotations that live in the view. The value of each of those keys is a JSON object which contains metadata specified for the annotation type. The example above specifies that the view contains Segment annotations and the metadata property unit is set to “seconds”. Section 2 will go into more details on how the vocabulary and the view metadata interact.

The medium key gives the identfier of the medium that the annotations are over.

The timestamp key reflects when the view was created by the tool. This is using the ISO 8601 format where the T separates the date from the time of the day. The timestamp can also be used to order views which is significant because by default arrays in JSON-LD are not ordered.

The tool key contains a URL that specifies what service created the annotation data. That URL should contain all information relevant for the tool: description, tool metadata, configuration etcetera. The tool URL includes a version number for the tool. It should also contain a link to the Git repository for the tool (and that repository will actually maintain all the information in the URL).

See https://github.com/clamsproject/mmif/issues/9 for a discussion on view metadata.

See https://github.com/clamsproject/mmif/issues/9 for a discussion on view metadata.

1.4.2. The view’s annotations property

The value of the annotations property on a view is a list of annotation objects. Here is an example of an annotation object:

{

"@type": "Segment",

"properties": {

"id": "s1",

"start": 0,

"end": 5,

"segmentType": "bars-and-tones"

}

}

The two required keys are @type and properties. The @type key has a special meaning in JSON-LD. Its value should be a URI that contains a description of the type that the annotation is of. Recall that he semantic context of the view allows the type to be expanded to the full URI. The example has Segment which will be expanded to http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocab/Segment, which is an element of the CLAMS vocabulary. For views that the LAPPS context you can use elements from the LAPPS vocabulary. See section 3 for user-defined annotation types.

The id key should have a value that is unique relative to all annotation elements in the view. Other annotations can refer to this identifier either with just the identifier (for example “s1”) or the identifier with a view identifier prefix (for example “v1:s1”). If there is no prefix the current view is assumed.

The properties dictionary typically contains the features defined for the annotation category as defined in the vocabularies at http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary or http://vocab.lappsgrid.org. For example, for the Segment annotation type the vocabulary includes the feature segmentType as well as the inherited features id, start and end. Values should be as specified in the vocabulary, values typically are strings, identifiers and integers, or lists of strings, identifiers and integers.

Technically all that is required of the keys in the properties dictionary is that they expand to a URI. In most cases, the keys reflect properties in the LAPPS vocabulary and we prefer to use the same name. So if we have a property segmentType, we will use segmentType in the properties dictionary. This implies that segmentType needs to be defined in the context so that it can be expanded to the correct URI in the vocabulary. And, in fact, the context has the following line that takes care of exactly that:

"segmentType": "Segment#segmentType"

So when using segmentType the full URI is http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/Segment#segmentType.

We allow arbitrary features in the properties dictionary. However, when an arbitray feature is used the semantic context as provided by the CLAMS and LAPPS vocabulary context will not have specific rules to expand the feature a sensible URI. For example, if we add a feature segmentLength the feature will be expanded to a generic http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/segmentLength. This is not horrible, but not ideal either, see section 3 on how to deal with annotation types and features that do not occur in the dictionary.

We have to be careful with properties that are defined on more than one annotation category. Say, for the sake of argument, that we have “pos” as a property on both the Token and NamedEntity annotation types in LAPPS. We then can use “pos” as the abbreviation of only one of the full URI and if we expand “pos” to http://vocab.lapps.grid.org/Token#pos then we need either use “NamedEntity#pos” or come up with a new abbreviated term. So far we have avoided this in CLAMS by having a property defined on one type only.

The annotations list is shallow, that is, all annotations in a view are in that list and annotations are not embedded inside of other annotations. For example, LAPPS Constituent annotations will not contain other Constituent annotations. However, in the features dictionary annotations can refer to other annotations using the identifiers of the other annotations.

Here is an other example of a view containing two bounding boxes created by the EAST text recognition tool:

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": {

"contains": {

"http://miff.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox": {

"unit": "pixels" }

},

"medium": "image3",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.io/east/1.0.4"

},

"annotations": [

{ "@type": "http://miff.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox",

"properties": {

"id": "bb0",

"coordinates": [[10,20], [60,20], [10,50], [60,50]] }

},

{ "@type": "http://miff.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox",

"properties": {

"id": "bb1",

"coordinates": [[90,40], [110,40], [90,80], [110,80]] }

}

]

}

}

1.5. More on the media property

NOTE: the contents here are all rather preliminary and further experimentation is needed.

Media can be generated from other media and/or from information in views. Assume the Tesseract OCR tool that takes an image and the coordinates of a bounding box and generates a new text for the bounding box. That text will be stored as a text medium in the MMIF document and that text can be the starting point for chains of text processing where views over the medium are created.

The alternative is to store the results in a view, but this introduces complextities when we want to run an NLP tool over the text since the text will then need to be extracted from the view first. In addition, it seemed conceptually clearer to represent text media as media, even though they may be derived.

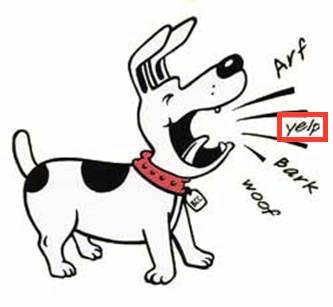

Let’s use an example of an image of a barking dog where a region of the image has been recognized by the EAST tool as containing text (image taken from http://clipart-library.com/dog-barking-clipart.html):

In MMIF, this looks like the following (leaving out some details, coordinates somewhat made up):

{

"media": [

{

"id": "m1",

"type": "image",

"location": "/var/archive/image-0012.jpg"

}

],

"views": [

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": {

"contains": {

"BoundingBox": {"unit": "pixels"}},

"medium": "m1",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.io/east/1.0.4"

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "BoundingBox",

"id": "bb1",

"properties": {

"coordinates": [[90,40], [110,40], [90,50], [110,50]] }

}

]

}

]

}

When we add results of processing as new media then those media need to assume some of the characteristics of views and we want to store metadata information just as we did with views:

{

"id": "m2",

"type": "text",

"text": {

"@value": "yelp",

"@language": "en"

},

"metadata": {

"source": "v1:bb1",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.io/tesseract/1.2.1"

}

}

Note the use of source, which points to a bounding box annotation in view v1. Indirectly that alo represents that the bounding box was from image m1. Other metadata like timestamps and version information can/should be added as well.

This glances over the problem that we need some way for Tesseract to know what bounding boxes to take. Either introducing some kind of type or use the tool property in the metadata or maybe introduce a subtype for BoundingBox like TextBox. In general, we may need to solve what we never really solved for LAPPS which is what view should be used as input for a tool.

Note that the image just had a bounding box for the part of the image with the word yelp, but there were three other image regions that could have been input to OCR as well. The representation above would be rather inefficient because it would repeat similar metadata over and over again. So we introduce a mechanism that in a way does the same as the annotations list in a view in that it allows metadata to be stored only once:

{

"id": "m2",

"type": "text/plain",

"metadata": {

"source": "v1",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.io/tesseract/1.2.1"

},

"submedia": [

{ "id": "sm1", "annotation": "bb1", "text": { "@value": "yelp" }},

{ "id": "sm2", "annotation": "bb2", "text": { "@value": "Arf" }},

{ "id": "sm3", "annotation": "bb3", "text": { "@value": "bark" }},

{ "id": "sm4", "annotation": "bb4", "text": { "@value": "woof" }}

]

}

The media set as a whole can be referred to with “m2”, and the submedia by concatenating the medium and submedium identifiers as in “m2:sm1”. Note how indivudual media have annotation properties that pick out the bounding box in the view that the text media were created from.

2. MIFF and the CLAMS Vocabulary

The structure of MMIF files is defined in the schema at http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/schema/mmif.json and described in this document. But the semantics of what is expressed in the views are determined by the CLAMS Vocabulary at http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary.

Each annotation has two fields: @type and properties. The value of the first one is typically an annotation type from the vocabulary. Here is a BoundingBox annotation as an example:

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox",

"properties": {

"id": "bb1",

"coordinates": [[0,0], [10,0], [0,10], [10,10]]

}

}

The value of @type refers to the URL http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox which is a page in the published vocabulary. That page will spell out the definition of BoundingBox as well as list all properties defined for BoundingBox, whether inherited or not. On the page we can see that id is a required property inherited from Annotation and that coordinates is a required property of BoundingBox. Both are expressed in the properties dictionary above. The page also says that there is an optional property timePoint but it is not used above.

The vocabulary also defines metadata properties. For example, the optional property unit can be used for a BoundingBox to specify what unit is used for the coordinates in instances of BoundingBox. This property is not expressed in the annotation but in the metadata of the view with the annotation type in the contains section:

{

"metadata": {

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/BoundingBox": {

"unit": "pixels"

}

},

"medium": "m12",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"tool": "http://tools.clams.ai/some_bb_tool/1.0.3"

}

}

Annotations in a MMIF file can also refer to the LAPPS Vocabulary at http://vocab.lappsgrid.org. In that case, the annotation type in @type will refer to a URL just as with CLAMS annotation types, the only difference is that the URL will be in the LAPPS Vocabulary. Properties and metadata properties of LAPPS annotation types are defined and used the same way as described above for CLAMS types.

3. MIFF Examples

The first example is at samples/example-1.json. It contains two media, one pointing at a video and the other at a transcript. For the first medium there are two views, one with bars-and-tone annotations and one with slate annotations. For the second medium there is one view with the results of a tokenizer. This example file, while minimal, has everything required by MMIF. A few things to note:

- The metadata specify the MMIF version and a top-level specification of what annotation types are in the views. Both are technically not needed because they can be derived from the context and the views, but are there for convenience.

- Each view has a context that is there to define the expanded forms of the terms in the annotations list. For example, the first view as an annotation object with @type equals TimeFrame. The context will expand this to http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/TimeFrame. Something similar happens to all property names in the properties dictionary.

- Each view has some metadata spelling out several kinds of things:

- What kind of annotations are in the view and what metadata are there on those annotations (for example, in the view with id=v2, the contains field has a property http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/TimeFrame with a dictionary as the value and that dictionary contains the metadata, in this case specifying that the unit used for annotation offsets is seconds).

- The medium that the annotations are over.

- A timestamp of when the view was created.

- The tool that created the view.

Note that only one annotation is shown for each view, this is to keep the file as small as possible. Of course, often the bars-and-tones and slate views often have only one annotation so it is only the tokens view where annotations were left out.

As we move along with integrating new tools, other examples will be added with other kinds of annotation types like BoundingBox and Alignment. Addition to the specifications will like accompany this. One thing we will know will change is the simple universe we show in the first example, where there are two simple medium instances and no submedia and annotations on submedia. For now we can get away with using start and end as properties that anchor an annotation, but we will probably replace those with something called anchor which provides several ways of anchoring annotations to the source: start and end offsets, start and end offsets qualified by submedia identifiers, coordinates, etcetera.

4. User-defined extensions

The value of @type in an annotation is typically an element of the CLAMS or LAPPS vocabulary, but you can also enter a user-defined annotation category defined elsewhere, for example by the creator of a tool. If a user-defined category is used then it would be defined outside of the CLAMS or LAPPS vocabulary and in that case the user should use the full URI because the context files will not take care of the proper term expansion. The same is true for any properties used that have meanings defined elsewhere.

Take as an example the following annotations.

{

"@type": "Clip",

"properties": {

"id": "clip-29",

"actor": "Geena Davis"

}

}

Each view is associated with a context and typically in a CLAMS view that context will help expand “Clip” to http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/Clip, but there is no such page in the CLAMS vocabulary. If third parties want to use their own definition they should use the full form. This is actually also the case for the properties, so if “actor” has a special meaning it should be fully qualified otherwise it will be understood as http://mmif.clams.ai/0.1.0/vocabulary/Clip#actor:

{

"@type": "https://schema.org/Clip",

"properties": {

"id": "clip-29",

"https://schema.org/actor": "Geena Davis"

}

}

Note how the “id” property does not have a full form and it will therefore be understood as a CLAMS or MMIF identifier.