MMIF is an annotation format for audiovisual media and associated text like transcripts and closed captions. It is a JSON-LD format used to transport data between CLAMS apps and is inspired by and partially based on LIF, the LAPPS Interchange Format. MMIF is pronounced mif or em-mif, or, if you like to hum, mmmmmif.

MMIF consists of two formal components in addition to this more informal specification:

- The JSON schema:

- The Vocabularies (the type hierarchies):

The JSON schema for MMIF defines the syntactic elements of MMIF which will be explained at length in “structure” section. These specifications often refer to elements from the CLAMS and LAPPS Vocabularies which define concepts and their ontological relations, see “vocabulary” section for notes on those vocabularies.

Along with the formal specifications and documentation we also provide a reference implementation of MMIF. It is developed in the Python programming language, and it will be distributed via GitHub (as source code) as well as via the Python Package Index (as a Python library). The package will function as a software development kit (SDK), that helps users (mostly developers) to easily use various features of MMIF in developing their own applications.

We use semantic versioning with the major.minor.patch version scheme. All formal components (this document, the JSON schema and CLAMS vocabulary) share the same version number, while the mmif-python Python SDK shares major and minor numbers with the specification version. See the versioning notes for more information on compatibility between different versions and how it plays out when chaining CLAMS apps in a pipeline.

Table of Contents

The format of MMIF files

As mentioned, MMIF is JSON in essence. When serialized to a physical file, the file must use Unicode charset encoded in UTF-8.

The structure of MMIF files

The JSON schema formally define the syntactic structure of a MMIF file. This section is an informal companion to the schema and gives further information.

In essence, a MMIF file represents two things:

- Media like texts, videos, images and audio recordings. We will call these documents.

- Annotations over those media representing information that was added by CLAMS processing.

Annotations are always stored separately from the media. They can be directly linked to a slice in the media (a string in a text, a shape in an image, or a time frame in a video or audio) or they can refer to other annotations, for example to specify relations between text strings. More specifically, a MMIF file contains some metadata, a list of media and a list of annotation views, where each view contains a list of annotation types like Segment, BoundingBox, VideoObject or NamedEntity.

The top-level structure of a MMIF file is as follows:

{

"metadata": {

"mmif": "http://mmif.clams.ai/1.0.5" },

"documents": [ ],

"views": [ ]

}

The metadata property stores metadata associated with the file. It is not heavily used for now, but we do use it to store the MMIF version used in the document. The mmif metadata property is required. You are allowed to add any other metadata properties.

The documents property

We assume that when a MMIF document is initialized it is given a list of media and each of these media is either an external file or a text string. These media are all imported into the MMIF file as documents of a certain type and the specifications for each medium/document is stored in the documents list. This list is read-only and cannot be extended after initialization. There are no limits on how many documents and how many documents of what types are in the list, but typically there will be just a few documents in there.

Here is an example document list with a video and its transcript:

{

"documents": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/VideoDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "m1",

"mime": "video/mpeg",

"location": "file:///var/archive/video-0012.mp4" }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "m2",

"mime": "text/plain",

"location": "file:///var/archive/transcript-0012.txt" }

}

]

}

The @type key has a special meaning in JSON-LD and it is used to define the type of data structure. In MMIF, the value should be a URL that points to a description of the type of document. Above we have a video and a text document and those types are described at http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/VideoDocument and http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument respectively. Currently, four document types are defined: VideoDocument, TextDocument, ImageDocument and AudioDocument.

The description also lists the properties that can be used for a type, and above we have the id, mime and location properties, used for the document identifier, the document’s MIME type and the location of the document, which is a URL. Should the document be a local file then the file:// scheme must be used. Alternatively, and for text only, the document could be inline, in which case the element is represented as in the text property in LIF, using a JSON value object containing a @value key and optionally a @language key:

{

"documents": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/VideoDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "m1",

"mime": "video/mpeg",

"location": "file:///var/archive/video-0012.mp4" }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "m1",

"text": {

"@value": "Sue flew to Bloomington.",

"@language": "en" } }

}

]

}

The value associated with @value is a string and the value associated with @language follows the rules in BCP47, which for our current purposes boils down to using the two-character ISO 639 code. With inline text no MIME type is needed.

The views property

This is where all the annotations and associated metadata live. Views contain structured information about documents but are separate from those documents. The value of views is a JSON-LD array of view objects where each view specifies what documents the annotation is over, what information it contains and what app created that information. To that end, each view has four properties: id, metadata and annotations.

{

"views": [

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": { },

"annotations": [ ]

}

]

}

Each view has a unique identifier. Annotation elements in the view have identifiers unique to the view and these elements can be uniquely referred to from outside the view by using the view identifier and the annotation element identifier, separated by a colon. For example, if the view above has an annotation with identifier “a8” then it can be referred to from outside the view by using “v1:a8”.

Here are a few general principles relevant to views:

- There is no limit to the number of views.

- Apps may create as many new views as they want.

- Apps may not change or add information to existing views, that is, views are read-only, which has many advantages at the cost of some redundancy. Since views are read-only, apps may not overwrite or delete information in existing views. This holds for the view’s metadata as well as the annotations.

- Annotations in views have identifiers that are unique to the view. Views have identifiers that uniquely define them relative to other views.

We now describe the metadata and the annotations.

The view’s metadata property

This property contains information about the annotations in a view. Here is an example for a view over a video with medium identifier “m1” with segments added by the CLAMS bars-and-tones application:

{

"app": "http://apps.clams.ai/bars-and-tones/1.0.5",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TimeFrame/v5": {

"timeUnit": "seconds",

"document": "m1"

}

},

"parameters": {"threshold": "0.5", "not-defined-parameter": "some-value"},

"appConfiguration": {"threshold": 0.5}

}

The timestamp key stores when the view was created by the application. This is using the ISO 8601 format where the T separates the date from the time of the day. The timestamp can also be used to order views, which is significant because by default arrays in JSON-LD are not ordered.

The app key contains an identifier that specifies what application created the view. The identifier must be a URL form, and HTTP webpage pointed by the URL should contain all app metadata information relevant for the application: description, configuration, input/output specifications and a more complete description of what output is created. The app identifier always includes a version number for the app. The metadata should also contain a link to the public code repository for the app (and that repository will actually maintain all the information in the URL).

The parameters is a dictionary of runtime parameters and their string values, if any. The primary purpose of this dictionary is to record the parameters “as-is” for reproducibility and accountability. Note that CLAMS apps are developed to run as HTTP servers, expecting parameters to be passed as URL query strings. Hence, the values in the parameters dictionary are always strings or simple lists of strings.

The appConfiguration is a dictionary of parameters and their values, after some automatic refinement of the runtime

parameters, that were actually used by the app. For the time being, automatic refinement includes:

- Converting data types according to the parameter specification.

- Adding default values for parameters that the user didn’t specify.

- Removing undefined parameters.

But refinedment process can be more complex in the future.

The contains dictionary has keys that refer to annotation objects in the CLAMS or LAPPS vocabulary, or user-defined objects. Namely, they indicate the kind of annotations that live in the view. The value of each of those keys is a JSON object which contains metadata specified for the annotation type. The example above has one key that indicates that the view contains TimeFrame annotations, and it gives two metadata values for that annotation type:

- The

documentkey gives the identifier of the document that the annotations of that type in this view are over. As we will see later, annotations anchor into documents using keys likestartandendand this property specifies what document that is. - The

timeUnitkey is set to “seconds” and this means that for each annotation the unit for the values instartandendare seconds.

Every annotation type defined in the CLAMS vocabulary has two feature structures - metadata and properties. See this definition of TimeFrame type in the vocabulary for an example. As we see here, contains dictionary in a view’s metadata is used to assign values to metadata keys. We’ll see in the following section that individual annotation objects are used to assign values to properties keys.

Note that when a property is set to some value in the contains in the view metadata then all annotations of that type should adhere to that value, in this case the document and timeUnit are set to “m1” and “seconds” respectively. In other words, the contains dictionary not only functions as an overview of the annotation types in this view, but also as a place for common metadata shared among annotations of a type. This is useful especially for document property, as in a single view, an app is likely to process only a limited number of source documents and resulting annotation objects will be anchored on those documents. It is technically possible for TimeFrame type to add document properties to individual annotation objects and overrule the metadata property, but this is not to be done without really good reasons. We get back to this later.

For annotation types that are used to measure time (such as TimePoint, TimeFrame, or VideoObject), the unit of the measurement (timeUnit) must be specified in the contains. However, for objects that measure image regions (such as BoundingBox.coordinates), the unit is always assumed to be pixels. That is, a coordinate is numbers of pixels from a point in an image to the origin along all axes, where the origin ((0,0)) is always the top-left point of the image. Similarly, for objects that measure text spans (such as Span.start/end), the unit of counting characters must always be code points. As mentioned above, MMIF must be serialized to a UTF-8 Unicode file.

Next section has more details on the interaction between the vocabulary and the metadata for the annotation types in the contains dictionary.

When an app fails to process the input for any reason and produces an error, it can record the error in the error field, instead of in contains. When this happens, the annotation list of the view must remain empty. Here is an example of a view with an error.

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://apps.clams.ai/bars-and-tones/1.0.5",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"error": {

"message": "FileNotFoundError: /data/input.mp4 from Document d1 is not found.",

"stackTrace": "Optionally, some-stack-traceback-information"

},

"parameters": {}

},

"annotations": []

}

Finally, an app may produce one or more warnings and still successfully process input and create annotations. In that case one extra view is added that has no annotations and that instead of the contains field has a warnings field which presents the warning messages as a list of strings.

{

"id": "v2",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://apps.clams.ai/bars-and-tones/1.0.5",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"warnings": ["Missing parameter frameRate, using default value."],

"parameters": {}

},

"annotations": []

}

The view’s annotations property

The value of the annotations property on a view is a list of annotation objects. Here is an example of an annotation object:

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TimeFrame/v5",

"properties": {

"id": "f1",

"start": 0,

"end": 5,

"label": "bars-and-tones"

}

}

The two required keys are @type and properties. As mentioned before, the @type key in JSON-LD is used to define the type of data structure. The properties dictionary typically contains the features defined for the annotation category as defined in the vocabularies at CLAMS vocabulary or LAPPS vocabulary. For example, for the TimeFrame annotation type the vocabulary includes the feature label as well as the inherited features id, start and end. Values should be as specified in the vocabulary, values typically are strings, identifiers and integers, or lists of strings, identifiers and integers, but can be more complex.

The id key should have a value that is unique relative to all annotation elements in the view. Other annotations can refer to this identifier either with just the identifier (for example “s1”), or the identifier with a view identifier prefix (for example “v1:s1”). If there is no prefix, the current view is assumed.

We will discuss more details on annotation type vocabularies in the “vocabulary” section.

The annotations list is shallow, that is, all annotations in a view are in that list and annotations are not embedded inside other annotations. For example, LAPPS Constituent annotations will not contain other Constituent annotations. However, in the properties dictionary annotations can refer to other annotations using the identifiers of the other annotations.

Here is another example of a view containing two bounding boxes created by the EAST text recognition app:

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://apps.clams.io/east/1.0.4",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4": {

"document": "image3"

}

}

},

"annotations": [

{ "@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4",

"properties": {

"id": "bb0",

"coordinates": [[10,20], [60,20], [10,50], [60,50]] }

},

{ "@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4",

"properties": {

"id": "bb1",

"coordinates": [[90,40], [110,40], [90,80], [110,80]] }

}

]

}

Note how the coordinates property is a list of lists where each embedded list is a pair of an x-coordinate and a y-coordinate.

Views with documents

We have seen that an initial set of media is added to the MMIF documents list and that applications then create views from those documents. But some applications are special in that they create text from audiovisual data and the annotations they create are similar to the documents in the documents list in that they could be the starting point for a text processing chain. For example, Tesseract can take a bounding box in an image and generate text from it and a Named Entity Recognition (NER) component can take the text and extract entities, just like it would from a transcript or other text document in the documents list.

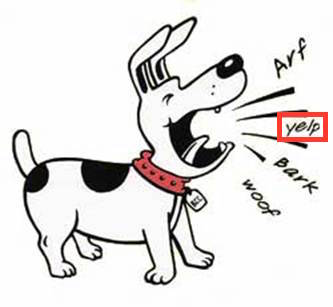

Let’s use an example of an image of a barking dog where a region of the image has been recognized by the EAST application as an image box containing text (image taken from http://clipart-library.com/dog-barking-clipart.html):

The result of this processing is a MMIF document with an image document and a view that contains a BoundingBox annotation where the bounding box has the label property set to “text”:

{

"documents": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/ImageDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "m1",

"mime": "image/jpeg",

"location": "file:///var/archive/image-0012.jpg" }

}

],

"views": [

{

"id": "v1",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://mmif.clams.ai/apps/east/0.2.2",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4": {

"document": "m1" } }

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4",

"properties": {

"id": "bb1",

"coordinates": [[10,20], [40,20], [10,30], [40,30]],

"label": "text" }

}

]

}

]

}

Tesseract will then add a view to this MMIF document that contains a text document as well as an Alignment type that specifies that the text document is aligned with the bounding box from view “v1”.

{

"id": "v2",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://mmif.clams.ai/apps/tesseract/0.2.2",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1" : {},

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Alignment/v1": {} }

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "td1",

"text": {

"@value": "yelp" } }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Alignment/v1",

"properties": {

"source": "v1:bb1",

"target": "td1" }

}

]

}

The text document annotation is the same kind of objects as the text document objects in the toplevel documents property, it has the same type and uses the same properties. Notice also that the history of the text document, namely that it was derived from a particular bounding box in a particular image, can be traced via the alignment of the text document with the bounding box.

An alternative for using an alignment would be to use a textSource property on the document or perhaps to reuse the location property. That would require less space, but would introduce another ways to align annotations.

Now this text document can be input to language processing. An NER component will not do anything interesting with this text so let’s say we have a semantic typing component that has “dog-sound” as one of its categories. That hypothetical semantic typing component would add a new view to the list. That semantic typing component would add a new view to the list:

{

"id": "v3",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://mmif.clams.ai/apps/semantic-typer/0.2.4",

"contains": {

"http://vocab.lappsgrid.org/SemanticTag": {

"document": "v2:td1" } }

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "http://vocab.lappsgrid.org/SemanticTag",

"properties": {

"id": "st1",

"category": "dog-sound",

"start": 0,

"end": 4 }

}

]

}

This view encodes that the span from character offset 0 to character offset 4 contains a semantic tag and that the category is “dog-sound”. This type can be traced to TextDocument “td1” in view “v2” via the document metadata property, and from there to the bounding box in the image.

See “examples” section with the MMIF examples for a more realistic and larger example.

We are here abstracting away from how the actual processing would proceed since we are focusing on the representation. In short, the CLAMS platform knows what kind of input an application requires and it would now that an NLP application requires a TextDocument to run on and it knows how to find all instance of TextDocument in a MMIF file.

Multiple text documents in a view

The image with the dog in the previous section just had a bounding box for the part of the image with the word yelp, but there were three other image regions that could have been input to OCR as well. With more boxes we just add more text documents and more alignments, here shown for one additional box:

{

"id": "v2",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://mmif.clams.ai/apps/tesseract/1.0.5",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1": {},

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Alignment/v1": {} }

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "td1",

"text": {

"@value": "yelp" } }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Alignment/v1",

"properties": {

"source": "v1:bb1",

"target": "td1" }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TextDocument/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "td2",

"text": {

"@value": "woof" } }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Alignment/v1",

"properties": {

"source": "v1:bb2",

"target": "td2" }

}

]

}

This of course assumes that view “v1” has a bounding box identified by “v1:bb2”.

Now if you run the semantic tagger you would get tags with the category set to “dog-sound”:

{

"id": "v3",

"metadata": {

"app": "http://mmif.clams.ai/apps/semantic-typer/0.2.4",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/SemanticTag/v1": {} }

},

"annotations": [

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/SemanticTag/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "st1",

"category": "dog-sound",

"document": "V2:td1",

"start": 0,

"end": 4 }

},

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/SemanticTag/v1",

"properties": {

"id": "st2",

"category": "dog-sound",

"document": "V2:td2",

"start": 0,

"end": 4 }

}

]

}

Notice how the document to which the SemanticTag annotations point is not expressed by the metadata document property but by individual document properties on each semantic tag. This is unavoidable when we have multiple text documents that can be input to language processing.

The above glances over the problem that we need some way for Tesseract to know what bounding boxes to take. We can do that by either introducing some kind of type or use the app property in the metadata or maybe by introducing a subtype for BoundingBox like TextBox. In general, we may need to solve what we never really solved for LAPPS which is what view should be used as input for an application.

MMIF and the Vocabularies

The structure of MMIF files is defined in the schema and described in this document. But the semantics of what is expressed in the views are determined by the CLAMS Vocabulary. Each annotation in a view has two fields: @type and properties. The value of the first one is typically an annotation type from the vocabulary. Here is a BoundingBox annotation as an example:

{

"@type": "http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4",

"properties": {

"id": "bb1",

"coordinates": [[0,0], [10,0], [0,10], [10,10]]

}

}

The value of @type refers to the URL http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/BoundingBox/v4 which is a page in the published vocabulary. That page will spell out the definition of BoundingBox as well as list all properties defined for it, whether inherited or not. On the page we can see that id is a required property inherited from Annotation and that coordinates is a required property of BoundingBox. Both are expressed in the properties dictionary above. The page also says that there is an optional property timePoint, but it is not used above.

You might also have noticed by now that these URL-formatted values to this key end with some version number (e.g. /v1), which is different from the version of this document. That is because each individual annotation type (and document type in documents list) has its own version independent of the MMIF version. The independent versioning of annotation types enables type checking mechanism in CLAMS pipelines. See versioning notes for more details.

As displayed in the vocabulary, annotation types are hierarchically structured with is-a inheritance relations. That is, all properties from a parent type are inherited to their children. The top-level type in the CLAMS vocabulary is http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Annotation, and it can be generally used for attaching a piece of information (annotation) to a source document, using document property to indicate the source document. If an annotation is specifically about (or derived from) a part of the document (for example, a certain sentence in the text or a certain area of the image, etc.), one should consider one of the Annotation’s children that can anchor to the part that suits semantics and purpose of the annotation. Again, the annotation object can (and probably should) use the document property with a source document identifier, as long as the type is a sub-type of the Annotation. We will see concrete examples in the below.

The http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/Thing type is designed only as a placeholder and is not intended to be used to represent actual annotations.

The vocabulary also defines metadata properties. For example, the optional property timeUnit can be used for a TimeFrame to specify what unit is used for the start and end time points in instances of TimeFrame. This property is not expressed in the annotation but in the metadata of the view with the annotation type in the contains dictionary:

As aforementioned, the Annotation type and its children can put the source document identifier in the contains dictionary, using document metadata property. Namely, there are two ways to express the source document of annotations: at individual object level or at the view level. Unless there is a good reason to specify document information for each and every annotation objects, using the view-level representation is recommended to save space when the MMIF is serialized to a JSON file.

{

"metadata": {

"app": "http://apps.clams.ai/some_time_segmentation_app/1.0.3",

"timestamp": "2020-05-27T12:23:45",

"contains": {

"http://mmif.clams.ai/vocabulary/TimeFrame/v5": {

"document": "m12",

"timeUnit": "milliseconds" } }

}

}

Annotations in a MMIF file often refer to the LAPPS Vocabulary at http://vocab.lappsgrid.org. In that case, the annotation type in @type will refer to a URL just as with CLAMS annotation types, the only difference is that the URL will be in the LAPPS Vocabulary. Properties and metadata properties of LAPPS annotation types are defined and used the same way as described above for CLAMS types.

Using a LAPPS type is actually an instance of the more general notion that the value of @type can be any URL (actually, any IRI). You can use any annotation category defined elsewhere, for example, you can use categories defined by the creator of an application or categories from other vocabularies. Here is an example with a type from https://schema.org:

{

"@type": "https://schema.org/Clip",

"properties": {

"id": "clip-29",

"actor": "Geena Davis"

}

}

This assumes that https://schema.org/Clip defines all the features used in the properties dictionary. One little disconnect here is that in MMIF we insist on each annotation having an identifier in the id property and as it happens https://schema.org does not define an id attribute, although it does define identifier.

The CLAMS Platform does not require that a URL like https://schema.org/Clip actually exists, but if it doesn’t users of an application that creates the Clip type will not know exactly what the application creates.

MMIF Examples

To finish off this document we provide some examples of complete MMIF documents:

| example | description |

|---|---|

| bars-tones-slates | A couple of time frames and some minimal text processing on a transcript. |

| east-tesseract-typing | EAST text box recognition followed by Tesseract OCR and semantic typing. |

| segmenter-kaldi-ner | Audio segmentation followed by Kaldi speech recognition and NER. |

| everything | A big MMIF example with various multimodal AI apps for video/audio as well as text. |

Each example has some comments and a link to a raw JSON file.

As we move along integrating new applications, other examples will be added with other kinds of annotation types.